Interviews

Tiriki Onus talks the journey to ABLAZE

23 May 2022

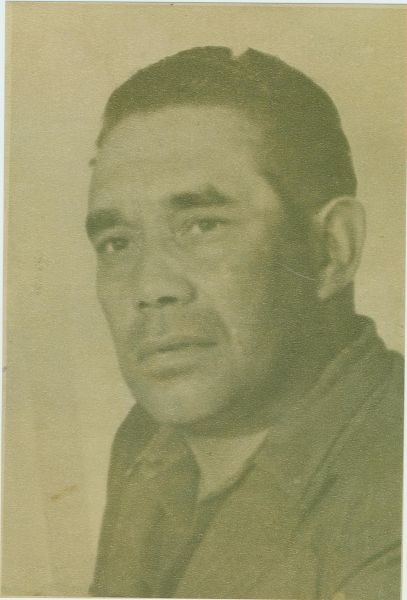

Umbrella is excited to release ABLAZE, in cinemas from May 26th. ABLAZE is a deeply impactful film starring Tiriki Onus and celebrates the life of his late Grandfather – academic, advocate, singer and filmmaker William ‘Bill’ Onus.

Tiriki details the incredible journey of discovery he documented with film maker and co-director of Ablaze, Alec Morgan below.

This article was originally published on screenhub.com.au

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this story contains video, voices and images of deceased persons.

Finding old family photographs in a suitcase is fairly common – almost infinitely less so that one of those pictures, combined with footage unearthed by a filmmaker, would lead to a feature-length documentary that tells the story of a key figure in Australian history.

This was the case for Tiriki Onus, a Yorta Yorta man, opera singer, artist and Head of the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development at the University of Melbourne, whose film ABLAZE premiered at the Melbourne International Film Festival last year and goes on general release this week.

More than six years in the making, and something of a detective story, the seed for the documentary was planted when filmmaker Alec Morgan contacted Onus with a strong hunch that a nine-minute black-and-white silent film he’d discovered in the National Film and Sound Archive was made by Onus’ grandfather, William ‘Bill’ Onus.

Bill was a Yorta Yorta/ Wiradjuri entrepreneur, boomerang champion, theatre impresario and political activist, who became the first Indigenous president of the Aborigines Advancement League in 1967 – and played a key role that same year in the referendum that allowed for Indigenous people to be included in the census.

For Onus, the timing of Morgan’s phone call was surreal.

‘We’d been discussing how a non-Indigenous filmmaker coming into Aboriginal communities and basically saying What stories do you want to tell? was a good example of inter-cultural collaboration,’ he says.

‘About half an hour later, I got a call out of the blue from Alec, who introduced himself and said, “Do you know your grandfather was the first Aboriginal filmmaker? I’ve found this film in the archives that I believe he made. Can I come down to Melbourne to show it to you?”‘

The find was all the more remarkable as the vast majority of films shot by Bill were lost in a caravan fire in the 1960s.

The near-confirmation of the film’s provenance, made more certain by the cross-checking of old family photographs, led to the pair working on the documentary that would eventually become ABLAZE.

In the absence of any supporting material or sound, it was initially tricky to date the film.

‘In the end, we were able to date parts of it to an exact month in 1946,’ Onus says.

From there, they were able to locate the records that would allow them to date, and better understand, intriguing footage of a theatre show that features in Bill’s film.

‘Bill had worked long and hard to challenge the neck-chaining of Aboriginal people in Western Australia, and that’s one of the things being depicted in the performance,’ Onus says.

‘It also shows people having rations withheld and women being abducted. And then, two non-Indigenous figures come on stage and dance along with the other actors, and there’s a judge and a court case being played out.

‘We discovered this production was put on as a collaboration between the Australian Aborigines League, of which Bill would later become president, and the New Theatre, a socialist worker’s theatre in Melbourne, in support of the Pilbara Strike in Western Australia, which began in 1946.’

The strike, which saw Aboriginal workers walk off pastoral stations in Western Australia to demand independence alongside better human rights, wages and working conditions, inspired the broader campaign for Aboriginal rights, of which Bill was very much a part.

In a twist, the research for ABLAZE was made easier by Australian intelligence operatives, who for some time had kept Bill (and many other activists) in their sights – his determination to keep Koori culture alive seen as a clear and present danger to non-Indigenous Australia.

‘We’re also really fortunate that ASIO started using movie cameras to record people and all of that footage is now in the public domain, which in so many ways is a wonderful testament to the work that Bill and others were doing,’ Onus says.

‘The humour and irony isn’t lost on me that, in doing so, ASIO actually created resources which are now empowering First Nations communities in reclaiming our culture, exercising our sovereignty and being self-determined. It’s a wonderful turnaround after all those years that they’re now able to supply us with resources to keep this work moving forward.’

In ABLAZE, Onus and Morgan travel to the Pilbara to show the film to descendants of the Pilbara Strike.

Observing theatre and film being used in such a powerful way by his grandfather has had a significant impact on Onus.

‘It’s made me feel good about the career and life choices that I’ve made to be in the space that I’m in now, too.’

The arts and their transformative potential form something of a through-line in Onus’s family – in his own case, he blends being a performer, visual artist and filmmaker with being a senior academic and advocate for Indigenous students in the arts.

His father, Lin Onus, was a celebrated painter, sculptor, and printmaker. His grandfather, Bill, in addition to his many other talents, set up a business called Aboriginal Enterprises in Melbourne in the 1950s, making items that showcased Indigenous designs.

Beyond art for art’s sake, Onus appreciates the role of art in protecting and promoting Indigenous culture both now and in the past.

‘It’s interesting that a lot of the work Bill and his contemporaries were doing in the early and middle part of the 20th century in cultural reclamation was about finding smart and innovative ways to practise culture and tell stories,’ he says.

‘For a lot of that time, across a lot of Australia, it was illegal for people to speak their language, to engage in ceremony and dance. Oftentimes, they weren’t even allowed to fraternise with their own family members.’

Beyond hoping that ABLAZE resonates with audiences, Onus would like it to help more stories to resurface.

‘I hope it spurs people to ask questions about what they’ve missed out on,’ he says, ‘living here, enjoying the benefits of this country and our communities, but at the same time wondering about the stories we could have been telling had all of us collectively, black, white, brindle, wherever we’re from, had the opportunity to engage more deeply.

‘I’m really pleased that opportunity hasn’t slipped away.’